For many of those following the writings of this "dithering old fool," who continues to hold an unfailing conviction in the strategic importance of gold and silver ownership in an otherwise out-of-control fiscal and monetary world, let me tell you a story about the 1970s.

I arrived in Saint Louis, Missouri, in the late summer of 1972, at the start of a magical four-year career as a student athlete at one of the top undergraduate business schools in the country. Populated largely by Jesuit educators, it also had many non-Jesuit professors in the twilight of their business careers that bestowed impressive anecdotes upon the collective psyches of the student population. In fact, it was a wonderful, coffee-sipping, Camel non-filter-chain-smoking finance professor who stood in front of the class in old De Smet Hall one morning, tripping the light fantastic about the implications of Richard Nixon abandoning the gold standard the year before and how it was going to cause massive inflation.

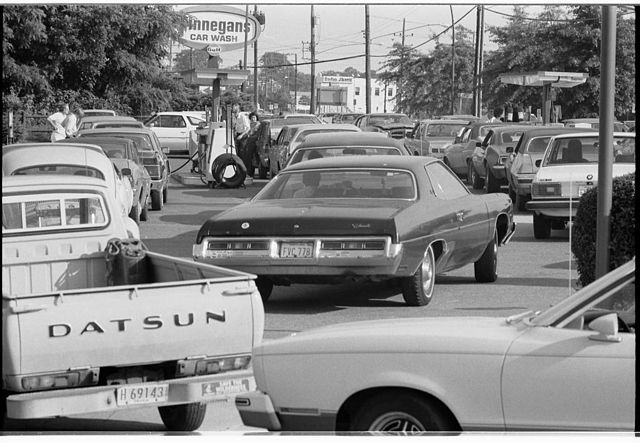

Within a couple of years, the U.S. was embroiled in a debilitating stagflation, where the cost-push effect on consumer prices was causing serious discomfort, resulting in labor union strife and stock market angst the likes of which created one of the longest and most damaging bear markets in history (the infamous 1973–1974 "bear").

In fact, one grizzled old sexagenarian, who was a stockbroker for Bache Halsey Stuart in the 1970s, told me that at his Toronto office, which employed a couple of dozen salesmen (they call them "wealth advisors" today) all making fistfuls of money in 1972, they arrived at work one day in 1974 only to find desks and telephones gone, replaced with a row of rotary-dial payphones that the now "part-time" brokers could use during lunch hour breaks from their full-time cab-driving jobs.

Even senior advisors at most brokerage firms today have no knowledge nor appreciation of what life is like in markets that operate without the safety nets provided by governments or government-sponsored entities like the Federal Reserve or the Bank of Canada. "Long live free market capitalism!" shouts former Trump advisor Larry Kudlow, as young people watched in horror how the illicit profits generated "doing God's work" (as Goldman Sachs' CEO Lloyd Blankfein once described his firm's mission) were classified as "private" until they blew up the banking system. It was at this exact point that the losses were magically "socialized," after which Kudlow was obligated to shift the narrative to "Long live free market cronyism!"

In the 1970s, the U.S. was trying to manage a crippling upward spiral in debt servicing costs caused by profligate "defense" spending during the Vietnam War, where the Fed monetized the cost of the U.S. military "offensive" spending by printing money. What started off as a recession in 1973–1974 soon metamorphosed into a full-blown inflationary spiral, and while most financial advisors were busy jamming low-yielding bonds into client portfolios, they did not fully grasp how a 5% coupon versus a 9% inflation rate could be harmful until their grandma's grocery bill had suddenly gone up 75% in six months.

What the Millennial and Gen-Xer investors fail to grasp is that the singular biggest driver for stocks since the bull began in August 1982 is a condition called "Goldilocks" — an economic parallel to the old fairytale where a young girl tastes three bowls of unattended porridge, with one too hot, one too cold, and the third "just right." This allegory has survived for four decades, with the American maestros relying on a ravaged middle class and cheap foreign imports to keep a lid on consumer prices while lowering borrowing costs to zero.

Each stock market cycle that included sharp corrections, like 1987, 1998, 2001, 2008 and 2020, have all been rectified with interventions and injections, where liquidity got sprayed across the financial forest fire, with the desired result being asset price inflation and stock market bliss. These rescues could never have happened in the 1970s because of two very distinct differences: baby boomers and inflation.

The disinflationary bias that has allowed stocks to flourish for the past four decades was the direct result of credit creation that fostered growth in business investment, which improved productivity, which allowed non-inflationary growth as products came to consumers more efficiently. Today, credit creation is fostering growth in asset investmentwithout productivity enhancements, with the result being massive increases in everything.

Contrary to popular delusion, the pandemic is not the cause of soaring grain, metal and lumber prices; "supply shock" is a fantasy used by Jerome Powell to facilitate his "transitory inflation" narrative. The similarities between the 1970s and the 2020s are strikingly obvious, but the pain of consumer price inflation is never appreciated fully by those who have benefitted from asset price inflation. When you look at the levels of incompetence in government responses to this "flu bug" circumnavigating the globe, the average worker who is no longer allowed to work has no money left and is soon to be deprived of his "stimmy."

Never before have I seen a witches' brew of social unrest and civil disobedience looming on the horizon than what I see today. The world needs a legion of Paul Volckers at the helm of fiscal and monetary navigation in order to protect the middle-class economies, as opposed to the privileged-class economies. The former thrives with business investment, while the latter influences, bribes and worships asset investment all financed by the credit creation machine, the global banking system or, as I prefer to call it, the politico-banco cartel.

The generational gap in understanding comes in the form of a loosely used term called "inflationary expectations," and while the citizens of Zimbabwe, Venezuela and Argentina have a superb, first-working knowledge of the perils of hyperinflation, the younger citizens of the West, and predominantly the USA, have never been exposed to anything resembling consumer price inflation, despite having been spoon-fed by the central bank a steady diet of asset price inflation since 2001.

The fact that huge numbers of Americans are making more staying at home than they would taking minimum-wage, burger-flipping jobs is just another example of government teaching them about the meaningless origins of "money," and demonstrating a total lack of respect for savings. The only "expectations" concerning inflation center around the Divine Right of the Unemployed to be granted a rich person's lifestyle by way of handouts, and until this Aura of Entitlement is replaced with the good, old Christian work ethic, wage inflation is going to be engaged in a footrace to outpace the stimmy cheques in order to attract workers.

It has been said that "80% of inflation is comprised of inflationary expectations," but the reality is that portfolio managers the world over are not old enough to have experienced the impact that expectations had on the global economy in the 1970s. The trader that had forty successful trades in Avon Products in 1972, between $110 and $140, got crushed with the 1974 bottom at $18.50. (I believe that Tesla in 2021 is the Avon of 1973–74.)

You have to have worn bell-bottom blue jeans (and thought you looked really cool) at some point in your life to fully grasp the economic damage that was caused by soaring input costs (rising producer prices). The components that contribute to a 70s-style outcome are seen everywhere today in consumer behavior, with housing once again on fire, rents on the rise, food prices soaring, and a blind Fed continuing to sell the "transitory inflation" meme that is gradually becoming a point of ridicule in the mainstream blogosphere.

I urge everyone reading this missive to adopt a "bunker mentality" when it comes to managing your investments, because the one singular event that caused the 1973–1974 bear market in the Dow Jones was the word "inflation," and while history may not repeat, it certainly rhymes. From a note by Jason Zweig back in 1997:

"But then (1973), in a crescendo of calamity, war broke out in the Mideast, oil prices quadrupled, Richard Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal, and inflation hit an annual rate of 12.2%. By December 1974, the Dow had plunged to 616, a 27.6% drop for the year."

Substitute "pandemic" for "war," "housing prices" for "oil prices," and you have the makings for an outcome not too far removed from that bear market. In dovetailing back to the "Goldilocks" allegory, 1973–74 was not a "Baby Bear;" it was not a "Mama Bear;" that bear market was the most agonizingly ursine "Grandpappy" bear market since the Great Depression.

Given current valuation levels, there is not a shred nor shadow of doubt in my mind that the world is going to experience an even more severe one in upcoming months, and while there will never be the air raid sirens of 1940s Britain to send us all to the Underground, prepare accordingly.

***

While it was fairly obvious to me at the time, it was investor sentiment for the precious metals that prompted my bold call back in early March, and then in late March (with a "double-down"), that gold prices had bottomed in the US$1,670/ounce range. As we are now nearly $200/ounce higher, I remain quite positive on the outlook for the summer months.

With every newsletter guru now doing podcasts on the "upcoming breakout in gold above US$1,850" (followed by 27 exclamation marks), I will probably reduce exposure into that because, as you all know, only in the gold and silver markets do we "sell breakouts" and "buy breakdowns." Why? Because those markets are completely "rigged."

So, now that you are all suitably spooked by my comments on the 1973–1974 comparison, remember the legendary stock "salesman" Jimmy Muir, who started loading his clients up with South African gold miners in 1973 and continued to do right up until 1977. He took mammoth amounts of grief from everyone (clients included) until late 1979, when his favorite stock, Vaals Reef Gold, hit $10 per share. You see, my young readers, he started buying the stock at US$0.70 per share, while the dividend was US$0.14 per annum, so while collecting a 20% yield in dividend income, he watched as gold prices rose and forced management to adhere to their stated "dividend policy" of a minimum 20% payout from net earnings. By the time gold hit US$800 in late '79, Vaals was earning an ungodly $3.50/share and yielding $0.70 in dividends.

But due to the apartheid problems in that nation in the late 70s, the P/E (price to earnings) multiple and the arrival of a new Fed policy by Paul Volcker forced Jimmy liquidate all client holdings in the gold stocks, and then retire comfortably, after which I lost touch, never to speak with him again.

Enjoy the weather; count your blessings; and let me know whether your bunker is staffed and prepared.

Originally published May 14, 2021.

Follow Michael Ballanger on Twitter @MiningJunkie. He is the Editor and Publisher of The GGM Advisory Service and can be contacted at miningjunkie216@outlook.com for subscription information.

Originally trained during the inflationary 1970s, Michael Ballanger is a graduate of Saint Louis University where he earned a Bachelor of Science in finance and a Bachelor of Art in marketing before completing post-graduate work at the Wharton School of Finance. With more than 30 years of experience as a junior mining and exploration specialist, as well as a solid background in corporate finance, Ballanger's adherence to the concept of "Hard Assets" allows him to focus the practice on selecting opportunities in the global resource sector with emphasis on the precious metals exploration and development sector. Ballanger takes great pleasure in visiting mineral properties around the globe in the never-ending hunt for early-stage opportunities.

[NLINSERT]Disclosure:

1) Statements and opinions expressed are the opinions of Michael Ballanger and not of Streetwise Reports or its officers. Michael Ballanger is wholly responsible for the validity of the statements. Streetwise Reports was not involved in any aspect of the article preparation. Michael Ballanger was not paid by Streetwise Reports LLC for this article. Streetwise Reports was not paid by the author to publish or syndicate this article.

2) This article does not constitute investment advice. Each reader is encouraged to consult with his or her individual financial professional and any action a reader takes as a result of information presented here is his or her own responsibility. By opening this page, each reader accepts and agrees to Streetwise Reports' terms of use and full legal disclaimer. This article is not a solicitation for investment. Streetwise Reports does not render general or specific investment advice and the information on Streetwise Reports should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Streetwise Reports does not endorse or recommend the business, products, services or securities of any company mentioned on Streetwise Reports.

3) From time to time, Streetwise Reports LLC and its directors, officers, employees or members of their families, as well as persons interviewed for articles and interviews on the site, may have a long or short position in securities mentioned. Directors, officers, employees or members of their immediate families are prohibited from making purchases and/or sales of those securities in the open market or otherwise from the time of the decision to publish an article until three business days after the publication of the article. The foregoing prohibition does not apply to articles that in substance only restate previously published company releases.

Michael Ballanger Disclaimer:

This letter makes no guarantee or warranty on the accuracy or completeness of the data provided. Nothing contained herein is intended or shall be deemed to be investment advice, implied or otherwise. This letter represents my views and replicates trades that I am making but nothing more than that. Always consult your registered advisor to assist you with your investments. I accept no liability for any loss arising from the use of the data contained on this letter. Options and junior mining stocks contain a high level of risk that may result in the loss of part or all invested capital and therefore are suitable for experienced and professional investors and traders only. One should be familiar with the risks involved in junior mining and options trading and we recommend consulting a financial adviser if you feel you do not understand the risks involved.