A few years after finishing high school in 1994, Steve Andersen found work building auto hoods and fenders in a loud, gritty auto plant in his hometown here. Today, he has a new job in town: supervising technicians in smocks and hairnets who create material for solar panels in a white-floored laboratory.

But Mr. Andersen is in the minority from benefiting from Fremont's clean-tech shift, however. Many of the new clean-tech arrivals employ lean staffs and have special exemptions on taxes.

"I don't know that you're going to be able to find a clear dollar connection" between the clean-tech arrivals and a boost in revenue for the city, says Lori Taylor, Fremont's economic-development director. Still, she adds that she hopes clean-tech companies will eventually become a new growth engine, along with new biotech and high-tech firms that also have cropped up in recent years.

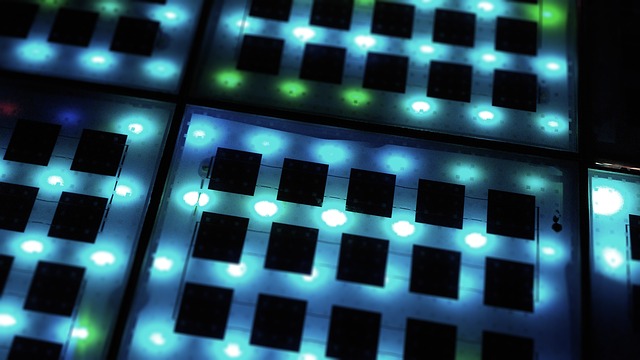

Overall, there were 20 clean-tech firms in Fremont in 2010, up from 12 in 2008 and six in 2006, according to Fremont's economic-development department. The city occupies a sweet spot for clean-tech companies because of its relatively low rents and abundance of buildings that combine offices, manufacturing and research-and-development, thanks to the city's manufacturing and high-tech legacy.

"You can't throw a Frisbee in Fremont without hitting another solar company," says Dan Shugar, chief executive of Solaria.

Yet most clean-tech firms in Fremont have tiny staffs and haven't grown as quickly as some hoped. All the clean-tech firms combined employ about 1,000 to 1,200 people full time in Fremont. Fremont's unemployment rate was 8.2% in November, compared with 9.3% nationwide.

"It's pretty bad," says Abel Martinez, owner of Taqueria Las Vegas, a Mexican restaurant across the street from the former Nummi plant, now called the Tesla Factory. "I haven't seen the new people."