Adrian Day: I think the topic is remarkably crucial and important. Everybody understands the main drivers behind the increase in resources prices, but most people, including those in the business, aren't yet fully grasping the scale of the resource shortage that I see coming. They know China's demand is going up. They know it's more difficult to get permitting and more difficult to find new deposits. But I don't think they really appreciate the extent of the problem.

TGR: What is the most important thing for investors to know?

AD: One of the keys is to really understand what kind of investor you are because what you buy and how you trade depends on that a lot.

- Can you tolerate risk? Or, will you panic if stocks decline 50%? Rick Rule, one of my friends in the business, keeps reminding us that volatility is a fact of life. How you use volatility determines whether you're successful. Make volatility your friend.

- How much time are you willing to devote?

- And frankly, how much money do you have to invest? If you don't have a lot of money, perhaps you want to be invested in one or two mutual funds. The more money you have, the more you can invest in different sectors and different areas.

TGR: You talk about this enormous resource shortfall. Surely, the U.S. doesn't appear to be on the brink of any boom. Why is it so big, especially considering that there was no shortage 5 or 10 years ago, when our economy was booming? Even China isn't growing at the rate it was.

AD: It doesn't matter whether the U.S. is booming or not. It doesn't matter whether Europe is booming or not. China has been driving the resource market and will continue to drive it for the next decade. That's what really matters; that's why I say it doesn't really matter if China's economic growth slows from 9.5%–5%. The demand for resources will still be very dramatic, and much higher than it is now. Just think about it. Everybody in China wants the same things we do. They want houses with electricity and running water and indoor plumbing. That takes steel and copper. If they move from a rural area into the city, at some point, they want a car. That takes aluminum and platinum, rubber for the tires and, of course, oil to run it. Obviously, cars are much more resource-intensive than bicycles and China is changing from bicycles to cars.

When countries industrialize, they tend to go through a characteristic pattern. Typically, the demand for commodities—resources—starts to grow as the GDP increases. It starts from a very low base and slowly over a period of 10–15 years, or even longer, it begins to gather momentum to double that level.

When the GDP reaches a certain level, though, the industrializing economies hit that takeoff point. Then the demand for resources starts to accelerate. For Japan in the 1960s and Korea in the 1980s, demand for most resources accelerated for a full decade until the economy industrialized and matured, and then the demand reached a plateau. The demand doesn't decline; it reaches a plateau. The critical thing is that demand for resources increases and accelerates at that takeoff but it increases on a per-capita basis because individual's needs and wants change. They go from bicycles to cars, from shacks to apartments, from open fires to stoves, from hanging up clothes to using dryers and so on. All these new wants require more resources than the old necessities. China represents 20% of the world's population. So unless its industrialization reverses—not slows down but reverses—the demand for resources is about to accelerate.

TGR: So slow acceleration brings an evolving country to a tipping point, after which the demand grows exponentially.

AD: Absolutely. And we could look at copper. . .at all of the resources. The pattern of consumption would be similar. It has much more significance than what happened in Korea or even Japan, because it's China—because of the population.

TGR: How do the other BRIC countries figure into your equation?

AD: India is a long way behind. India today is about where China was 10 years ago. As China's economy reaches a mature stage—mature in terms of the consumption of commodities, which probably will be 10–15 years from now—India will be just about at that takeoff point.

TGR: So, we have two tidal waves coming?

AD: Absolutely. India right behind China, and then Brazil and another country with a large population, right behind India.

TGR: Why aren't the general investment markets seeing this?

AD: I think that in very long-term, dramatic trends, people always tend to be playing catch-up. You see it with individual companies with big discoveries that continue to grow. The stock price goes up, but it's still good value because investors also generally have difficulty with a big trend getting ahead of them. Their understanding of it is always lagging.

TGR: What makes your book different?

AD: My book is very much a primer, if you like, not aimed at experts in the field but rather for educated investors who don't really know much about resources. I think it is particularly helpful for newer investors, or investors who are new to resources, because I try to write without jargon. I'm not trying to show people how clever I am. I'm trying to make it understandable to ordinary, intelligent people who know a little about investing but don't necessarily know anything about resources. So I think that's one thing that makes it different. It's very accessible. I don't cover every single resource out there but I try to cover the main resource areas in separate, short chapters. I try to help people with practical advice.

TGR: You've talked a lot about quantitative easing in the U.S. in conversations, lectures and interviews. How does that factor into the trend toward higher commodities prices?

AD: There are always two major areas to consider any time you look at commodities—the supply/demand factors and the overall economic environment. Other things being equal, a declining dollar means higher commodity prices. More money being put into the system and low interest rates mean higher prices for commodities. Well, guess what? We've got a falling dollar, more money being put into the system and low interest rates. So, we have the perfect economic environment on top of the perfect supply/demand situation.

TGR: An accelerant on the flames.

AD: I have no doubt that, at some point in the next few years, we're going to see an upward, albeit temporary, correction in the dollar. I have no doubt that we're going to see a slowdown in China. When China's GDP growth drops from 9.5%–5%, 4% or 3%, everybody will think the world's ending—but that's still pretty good, positive growth. But it wouldn't surprise me if we had setbacks. Let's not forget that during the U.S. industrialization from 1870 to the start of World War I, the U.S. had a depression, a recession, strikers getting shot in the streets—all sorts of problems. Think of England's industrialization after the Napoleonic War, from 1815–1840, when Britain transformed from an agrarian to an industrial economy. Again, recession, deflation, the Peterloo Massacre. . .all sorts of problems going on intermittently. I have no doubt that will happen in China, too; but if you take the big-picture view and don't let these setbacks scare you, you'll look back to see that they only last a short period of time. They're just interruptions in the big theme.

TGR: Right.

AD: Resources are more cyclical than most things and there are basic economic reasons for that. If you look back in history, the longest sustained periods of rising prices for commodities across the board always can be identified by a new source of demand—not a shortage. So, if you look at resources from 1870–1914, when both the U.S. and Germany were industrializing, you see a long upward move in resources. The same goes for the period from 1815–1840.

Investors must understand major market drivers and why the industrialization of China, and the growing middle class that goes with it, are so important. People in cities use more resources than people in the countryside. Middle-class people buy things that use more resources than poorer people, etc.

If we come into a slowdown, look at whether those major drivers have reversed and are no longer valid. Is this the end or just a temporary slowdown? If you agree that this is a long-term super cycle, don't let the corrections scare you.

Corrections can be very sharp and severe. Gold declined 50% from 1973–1974. A lot of people freaked out and sold right at the beginning of the second leg up, which, of course, was the biggest leg up. Similarly, commodities corrected very, very sharply in 2008—and many investors panicked, sadly; but the key is that they bounced back very quickly, as well. I think that was a reflection of the real fundamental demand in China. Of course, at the end of 2008 huge inventories had been built up both there and in London. An exaggerated move in commodities prices resulted when speculators got in and hedge funds built up.

When the prices started to correct, the decline also was exaggerated because not only was there slowdown in fundamental demand, but also a depletion of the inventories and hedge funds and speculators were dumping at the same time. Despite all of that, resources bounced back very, very quickly. Copper came back. Aluminum came back. It was not because the U.S. economy had a huge rebound; they came back purely because of Chinese demand. It wasn't speculation, it was real demand.

TGR: What basic strategies do you tell people to employ?

AD: The main strategic advice I give to people is to be really careful not to sell out too soon. I believe this is a multiyear bull market in resources. We'll see resources prices go much higher. I don't want to sound as if I'm waving my arms because I don't normally talk that way. Still, over 5, 10, 15 years, I think prices will go higher than we can imagine right now. Part of that will be in deflated dollars, of course; but if you buy quality companies with sound balance sheets that own resources in the ground in good jurisdictions, avoid the temptation to sell when the stock moves a little bit. You may not have the opportunity to buy back.

TGR: Here at the Hard Assets Conference, when we hear the term "resources," we can probably figure we're talking about mineable materials. Is that how you define resources? Or, do you mean something broader?

AD: I must admit I am switching around a bit between the words "resources" and "commodities," but in this context I'm talking about everything from the precious metals to the base metals to energy—oil, gas, uranium, geothermal; and when we say "commodities" we include agriculture. I think agricultural assets will be among the best-performing assets over the next decade.

TGR: You mentioned selling and not selling too soon. How do you strike a balance between taking some money off the table—taking profits—and staying in the game long enough to maximize what you should maximize?

AD: That's always a critical decision. When we buy shares for a client, we know in advance whether it is likely to be a core holding or a trading stock. As Doug Casey would put it, we know whether it's an 'eating sardine' or a 'trading sardine.' Obviously, you want to get rid of the trading sardine before it starts smelling.

TGR: Any examples come to mind?

AD: Sure. If you have a big position in Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. (NYSE:FCX), that would be a core holding, an eating sardine, and I'd be pretty cautious about selling it. I certainly wouldn't sell all of it. If the stock moved to a point where I thought it was just overpriced and other copper companies started looking particularly attractive relative to Freeport, I would start to trim the Freeport but I certainly wouldn't sell it all. I would only sell out if something dramatic happened, such as a major change in strategy or something fundamental happened to change the company.

TGR: Does that philosophy apply to micro-cap stocks?

AD: No, absolutely not. Freeport's market cap is upwards of $46 billion. Micro caps are at the other end of the spectrum. The situation is the opposite when you have a small company that needs to keep raising money and is mostly dependent upon a single asset. In that case, I think you'd want to be much more of a trader.

I'm not a geologist and I don't have technical training, so I tend to favor companies not for a particular property or whether the geology looks good but because they have a good business plan, a diversity of assets, good management, a sound balance sheet and so on. With them, you're not buying a specific property with a particular drill hole or drill-hole season. When we do buy companies that depend on a single property, we tend to be very quick at selling on either good or bad news.

TGR: Does your new book focus more on these micro caps or the major players?

AD: Both. The first part of the book talks about the whole macro issue—supply difficulties, demand and where it's coming from and how resources act during both deflations and inflations. It talks about how economic factors affect resources, and then it goes into each particular sector—oil, gas, uranium, coal, etc.—for both big and small companies.

TGR: Any examples of those?

AD: Not really, because I don't spend a lot of time in the book discussing individual companies simply because things change so much. In fact, I'd written about some companies in the manuscript that I sent in to my publisher in March and when they sent me the pages back for final editing in May, two of them had been taken over. So it just doesn't make sense in a market like this to talk a lot about junior companies.

TGR: More broadly speaking, does your buy-and-hold strategy apply to resources?

AD: I don't think you can afford to be exclusively a buy-and-hold investor in the resource area because these stocks are so volatile. It also depends on what sector of the market you're looking at. Let me step back a bit. Considering the enormous increases in commodities prices I foresee over the next 10 years, I think you want to be exposed. You don't want to try to be too clever and trade only to find that you missed out on a big move. The moves can come very quickly. I know an awful lot of people who panicked and sold at the end of 2008. By the time they finally bought back into the market, they paid double or triple their selling prices. In other words, I'd avoid the temptation to get out of the sector altogether.

There are times to be more heavily invested in copper and times to be more heavily invested in oil. Focus on commodities that are particularly cheap and attractive right now. When they get expensive and perhaps less attractive, reduce your exposure. So, certainly you're trading on the various sectors as time goes on. Particularly the juniors, I think you want to be active and you want to take profits. No question.

TGR: What other sectors will benefit from the growth in China and India?

AD: Look at where people spend their disposable income and the effects of a growing middle class. Typically, when you have a poor rural country you have very rich and very poor but a very small middle class. When the economy industrializes, the middle class grows. For example, 15 years ago Brazil had a very small middle class—a lot of very wealthy and a lot of very poor. Brazil still has a lot of very wealthy and a lot of poor, but many of them have gone from abject poverty to barely scraping by. They're poor but a lot better off than they were. And there's a growing middle class.

Now, one effect of this growing middle class in Brazil has been on the mortgage business. One stock we own is Gafisa SA (NYSE:GFA), the third largest Brazilian residential construction and real estate company, which is also a mortgage lender. Just 10, 15 years ago, there were virtually no residential mortgages in Brazil. Basically, the residential mortgage business did not exist.

TGR: Why was that?

AD: Well, 15 years ago the country had just torn up its second currency. It had 500% inflation and 50% interest rates. Would you want to borrow if interest rates were 50%? Or, would you want to lend for 30 years if you had two currency changes in 10 years and inflation at 500%? Now that inflation is down to about 5% or 6%, the real is a strong currency and interest rates—while still higher than most countries—are at a much more reasonable level, 10%–12%. So, people now are prepared to borrow money and people are prepared to lend it. It's not that people in Brazil didn't want to own a house. Everybody wants to own a house. It just didn't make economic sense. Even today, mortgages represent just 3% of GDP compared with more than 10% in Mexico and Chile. For the first time, 30-year mortgages have been introduced. So, there's still tremendous growth potential even if the economy didn't continue to grow.

TGR: You just mentioned one company in your portfolio. Adrian Day Asset Management has both gold and resource accounts. What are some of the core holding in those?

AD: In the gold accounts, we have about 25%–30% in the seniors and about 30% in pure explorers. We also have some in GLD or in gold bullion, depending on which is appropriate. The rest is in juniors, smaller producers, etc. In my investing for clients, I tend to look for the simplest and most direct way of investing. If I can find a really quality company that is an obvious choice, I stop there. Why go further down the food chain? In some of the other commodities—let's say uranium—the obvious choice is not necessarily a great company. So, I'd look at some options to Cameco Corp. (TSX:CCO; NYSE:CCJ). But in copper, for example, Freeport is great. It's the biggest public copper mining company in the world and it has great assets, diversified assets. It has a great balance sheet, good management and it pays a great dividend. Why go any further?

TGR: How about in gold?

AD: Virginia Mines Inc. (TSX:VGQ) is still one of my largest holdings.

TGR: Did you happen to see André Gaumond (Virginia's president and CEO) at the Hard Assets Conference?

AD: Yes. I was glad to see him. I had dinner with him on Sunday, actually. You can speak to every single person in the business and not one has a bad thing to say about André Gaumond or Paul Archer (VP, exploration). They are well regarded by everybody. It's not just a plug for Virginia but it explains the sort of thing we look at. Again, I'm not a geologist, so what attracts me to Virginia is not its properties. If you asked me about the company's properties, I could tell you maybe a sentence about each. It’s not the geology of the properties. Virginia obviously has great management with a great track record. But it's the business plan. It's not a pure joint venture (JV) company, but it has a strong balance sheet and $44 million in cash and money coming in. The cash coming in from the JVs it manages gives it the cash flow to put money into the ground and not have to keep going back diluting shareholders. Where it sees key properties it likes, the company can afford to put money into exploration without always coming back to the market. That's the key.

To me, the key in juniors is the dilution. If you're not getting income, you must have dilution, either at the company or property level. The question is: Which is better? You want to avoid diluting shareholders continually and exaggeratedly. The traditional model, of course, is to raise money, drill a hole and go back saying, "Hey, we have some good results. Give us more money," drill another hole, go back, etc. Some companies have gone back two or even three times in the same year—and that's a big drag on their stock prices. The model I like minimizes that to an extent or even avoids it.

TGR: You said you could give us a sentence or two about Virginia's properties?

AD: The company's biggest asset outside the $44M in cash is the royalty it owns on Goldcorp Inc.'s (NYSE:GG; TSX:G) Éléonore Property. The last resource estimate Goldcorp put out at the beginning of this year actually doubled the resource, bringing it up to 9.4 million ounces (Moz.)—but it's going to be bigger than that. You can do a net present value on a royalty quite easily using a discounted cash-flow model. Make an assumption on a gold price and a discount rate, and then you know what the thing is worth today and what someone else would be willing to pay for it. At $1,100 gold steady with a 5% discount, it's worth about $180 million. Add the $180M to the $44M and you find that those two assets alone equal or actually exceed the market cap of the entire company; it has no debt, so everything else comes free, including a zinc deposit, which is just sitting on the shelf. It's free; that and the 4 Moz. gold resource it owns at different projects—all free. Its JVs—all free. I like free; so not only would I buy Virginia now, it's an example of my ideal kind of company. Not relying on a particular project or a drill hole, I'm betting on Virginia. I'm patient. I don't mind how long I have to wait. Whether it wins this year, next year or three years from now, I think Virginia will win. In the meantime, the downside is very limited because the stock's selling for less than that asset value. I like that kind of model where the downside is low and the upside's just a matter of time.

TGR: And doesn't the royalty actually increase when Éléonore goes into production?

AD: Oh, yes. Right now, they're just getting $100,000 a month I think. Actually, it's unusual even to have advance payments. But when Éléonore goes into production, which is scheduled for 2014, the royalty goes up. As the production goes up and the price of gold goes up, the royalty actually goes up to 3.5%. That would be a very, very attractive royalty—cash flow that is also profit.

TGR: Any other gold companies on your go-to list?

AD: Another company similar to Virginia would be Midland Exploration Inc. (TSX.V:MD). It's much smaller, about $30 million in market cap.

TGR: Also a project generator.

AD: Virginia started out with the same model. It was pure project generator, but now it's big enough it can afford to take on more risk itself. Midland has five JVs with Agnico-Eagle Mines Ltd. (TSX:AEM; NYSE:AEM), Osisko Mining Corp. (TSX:OSK), North American Palladium Ltd. (TSX:PDL; NYSE:PAL), Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) and Zincore Metals Inc. (TSX:ZNC). So, it has JVs in zinc, rare earth elements (REEs) and gold. It also has JVs with other companies spending the money on gold, and several gold properties. Gold is a dominant one. The REE business is particularly attractive because JOGMEC is already drilling the property in an extremely aggressive program on a $13M budget. This doesn't guarantee it'll find anything; but, if it decides to back out, we'll know the company gave its best shot. That's all you really want from a JV partner.

So Midland has multiple projects and multiple resources with numerous different partners, plus a good balance sheet. It's only about $4.5M–$5M, but that's more than enough for now. It's continuing to generate new projects, so I like Midland an awful lot. It's trading at about $1.77 right now. Frankly, I wouldn't chase the price too much; but with a good company like that, your surprises are always more likely to be on the upside. That's why I'm a little less price sensitive than with a pure drill-hole play.

TGR: Have you added any new companies to your list recently?

AD: Over the last few months, we've bought a lot more new companies in the global markets, particularly in the emerging markets and the resource area. We are buying the Renaissance Gold Inc. (TSX.V:REN)—a spinoff of AuEx Ventures, which was acquired by Fronteer Gold Inc. (TSX:FRG; NYSE.A:FRG). I like the Renaissance Gold business plan. The company's got a good balance sheet, successful people like Ron Parratt; I like the management a lot.

We've also been buying Mirasol Resources Ltd. (TSX.V:MRZ), which just started drilling a highly prospective silver project in Argentina. It has great management and a strong balance sheet. However, given the excitement surrounding silver, the stock price is now discounting a fair amount of success on this project, so I wouldn't buy now. The problem right now is that most stocks are no longer a good value—not even the best companies, or they are discounting success that may or may not happen.

Believe me, I'd much prefer to be rattling off lists of companies and proclaiming them all great buys. It's more fun for me, and certainly more fun for your readers. But that's not the way it works. And right now, we have to be selective and patient.

TGR: Are you buying anything today?

AD: One of my favorites in the general resource area is Sprott Resource Corp. (TSX:SCP). If you buy Sprott, which is quite a liquid company, you're getting it at a discount to net asset value (NAV). NAV is about $5.20; the stock's been trading at about $4.35. You're also getting great management—Kevin Bambrough and company—and a great balance sheet.

Sprott has direct and indirect investments in different resource areas, buying whole companies, sponsoring companies or growing them. The four main areas it's in now are: 1) gold, primarily gold bullion; 2) oil and gas; 3) agriculture; and 4) fertilizer. When the companies reach a certain level, ideally it will spin off a certain amount of the shareholding in a public company. Sprott is extremely disciplined and has done this a few times already. This is a great buy right now at today's price; it's depressed due to a significant warrant issue that expires December 31, so I don't expect this weakness to last.

TGR: Any others?

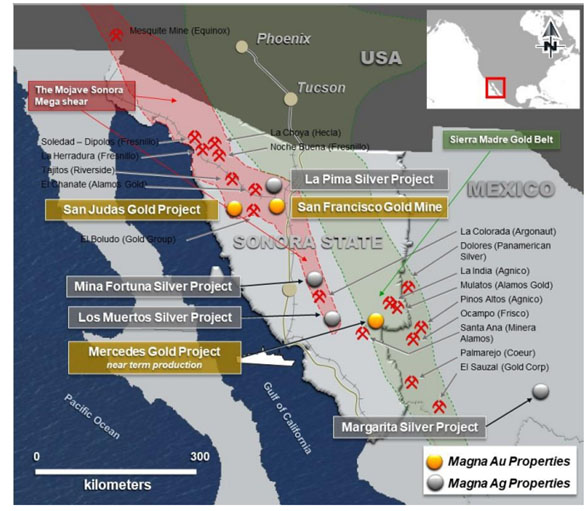

Evrim Metals Corporation is a private company now, but it's going to go public after a reverse takeover in probably the first or second week of January. Evrim was put together by some pretty good people, one of whom was Paul Van Eeden, with Paddy Nicol as CEO, who were instrumental in putting a deal together for Evrim to buy the Mexican assets of Kiska Metals Corp. (TSX.V:KSK). In addition to Kiska's properties, Evrim also got all of its Mexican geologists. They are planning to follow the classic model of drilling the properties a bit, and then joint venturing them to bring money in. Hopefully, there won't be much dilution. So, I like that one a lot. Good people, good balance sheets, good properties and a great business plan.

TGR: That sounds like something worth waiting for, too.

AD: Yes, it is, but it might also be worth saying that the first day of trading is not necessarily the best day to buy it when a widely anticipated company actually comes out.

TGR: Many times, it's the worst.

AD: Well, I'm English so I understate things but there's always pent-up buying pressure.

TGR: Do you recommend ETFs?

AD: Yes, but there are pitfalls. The ETFs are not necessarily the best way to play. GLD, the gold ETF, is a great way to play gold and Uranium Participation Corp. (TSX:U), which is a closed-end fund not an ETF, of course, is a great way to directly play uranium. But I don't think the commodity ETFs are the best way to play other commodities because, by and large, they invest in futures contracts, not the commodities themselves. With some commodities, oil in particular, you have very high contangos—the difference between forward and spot prices. So, they're continually rolling over contracts at higher prices. Oil is a classic example; the oil ETF has actually lost money over the last four years even though the price of oil has done quite well. They're always buying high and selling low, which is not exactly the road to successful investing.

TGR: Anything you'd like to wrap up with?

AD: Every single commodity is going to participate to greater or lesser extent—precious metals, base metals, energy, uranium, geothermal, agricultural, water, copper, zinc. . .everything. With some things, the fundamentals aren't quite as strong as with others; some things are perhaps a little too expensive already.

Copper is one that typically moves early on, at the beginning of industrialization, because copper is used for infrastructure construction and for power plants. Copper is still very, very strong; in a couple of years time, zinc will be very strong. We have excess uranium supply and capacity right now and the possibility of Cigar Lake coming on. But the point is, if you look at supply/demand, China's huge demand growth has not yet started but the supply is already quite strong, quite ample. The really big crunch for uranium will come in the second half of the decade when China's demand ramps up, some of the excess capacity has been used and some of the big mines have started to mature and decline a little bit.

TGR: And your investment advice as this picture takes shape?

AD: Markets anticipate, so you want to be accumulating zinc and uranium even though the supply/demand crunch isn't there yet. But because you've got a few years, be a little more sensitive on the price.

Adrian Day, London born and a graduate of the London School of Economics, heads the eponymous money management firm Adrian Day's Asset Management (P.O. Box 6643, Annapolis, MD 21401; www.adriandayassetmanagement.com; assetmanagement@Adrianday.com; 410-224-2037 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting 410-224-2037 end_of_the_skype_highlighting) where he manages discretionary accounts in both global and resource areas. His latest book, just published, is Investing in Resources: How to Profit from the Outsized Potential and Avoid the Risks (John Wiley & Sons), available from bookstores or from Amazon and other online booksellers.

Want to read more exclusive Gold Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you'll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Expert Insights page.

DISCLOSURE:

1) Karen Roche and Brian Sylvester of The Gold Report conducted this interview. They personally and/or their families own the following companies mentioned in this interview: None.

2) The following companies mentioned in the interview are sponsors of The Gold Report: Goldcorp, Kiska, Midland and Renaissance.

3) Adrian Day: I personally and/or my family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview: None. Clients for whom I manage money own all companies mentioned. I personally and/or my family am paid by the following companies mentioned in this interview: None.