Durendal Resources Inc. says the model for mineral exploration no longer works and its machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) tools can quickly identify high-grade opportunities and give geologists better big picture views of what's under the surface.

Since the 19th century, the process of prospecting has changed little — before anything can be mined from the ground, much time, effort, and money must be spent trying to find where the resources are. This can require drilling, geophysical mapping, metallurgical testing, and other procedures to narrow in on deposits that geologists can't physically see underground.

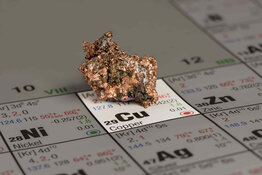

One of Durendal's standout projects is a new high-performance web-based Geographical Information Systems (GIS) platform that will act as an interface for the data and provide real-time information, cutting down exploration time as companies search not only for precious metals but also the critical metals needed for the transition to a cleaner economy like copper.

As Durendal Chief Executive Officer Colby Mintram told Streetwise Reports, "Junior exploration … wastes money."

"It's like putting a blindfold on spinning in a circle 1,000 times and then throwing a dart with your non-dominant hand at a dartboard 1,000 meters away and expecting to hit it," Mintram said of looking for top-paying resources. "It's just the odds of success are just so incredibly low."

Exploration is the first part of the life cycle of a mine, which also includes discovery, development, production, and reclamation. Companies like Durendal and KoBold Metals are zeroing in on exploration and discovery, hoping that AI and machine learning can help geologists find what they're looking for, from gold to the rare earth elements needed for super magnets.

Durendal's platform will allow users to access the data they want instantly in 2D, 3D, and 4D without data restrictions.

The Catalyst: Seeing Underground

Finding resources in our ancient past involved much less effort — it was simply the search for the best stones to make tools with, the oldest about 2.6 million years old. However, natural resources eventually had an impact on where humans settled, with the earliest known mine for a specific mineral (coal) in southern Africa 40,000 to 20,000 years ago.

Some scientific methods of exploration were put into use during the Middle Ages with more systemic exploration, and the Industrial Revolution created a huge demand for coal, iron, and other minerals.

"The 20th century marked a significant turning point, as advancements in technology, like satellite imagery and geophysical surveys, transformed mineral exploration, making it more precise and efficient," according to a Q&A on Pheasant Energy's website.

Discoveries rely on "good fieldwork, quality geoscience, investment, and planning to bring them to the development stage," according to the Nova Scotia Department of Resources website.

"The mine development stage includes feasibility, geoscience, and engineering studies," the site said. "If all of these outcomes are favorable and all approvals are in place, the company then decides if they will go ahead with the project."

However, since techniques used to zero in on those resources don't give scientists a complete look at what's under the ground, many projects don't get to this stage.

According to Durendal, 65% of all mineral deposits are discovered by junior exploration companies, but they are 90% Tier 3 projects or lower (net present value of US$200 million or less). Tier 1 projects are worth more than US$1 billion.

"Discovery is sort of like putting together a puzzle," Mintram said. "If you don't have all the puzzle pieces, you're going to be very, very frustrated when you go to go to put it together."

Quick, Easy Analysis

So, what's the issue? Mintram said it's all in the data and the way they are used by geologists. Massive amounts of public information are available in addition to results collected on mineral projects through drilling and other means, but crunching the numbers takes time, sometimes months.

The U.S. Geological Survey, for example, has many databases for variables nationwide. But they are not natively exportable into other geographic information systems (GIS) programs. The data is also intensive and results can load slowly.

That's where the speed of supercomputing in the cloud and the power of machine learning and AI comes in. Durendal uses a "probabilistic approach "integrating hundreds of layers of data to independently weight the variables against each other," Mintram said.

"It's marrying that man and machine so that the machine does a lot of the heavy lifting," he continued. "That's currently done by geoscientists (and) … wastes way too much of their time."

Its system takes in massive amounts of geology data, everything from PDFs, images, and videos to raster files, and uses cloud supercomputing to run the millions of calculations required to allow quick and easy retrieval of an analysis.

It can be as easy as going to a computer map, drawing a box around an area, selecting what data to include, and then exporting to a GIS-compliant file. "It took you five minutes to do," Mintram said.

Creating such computing power would be cost-prohibitive for individual companies to build from scratch. That's where cloud computing comes in. Durendal is a member of Microsoft's for Startups program and has US$500,000 worth of free cloud computing.

"You can build a supercomputer in the cloud," Mintram said.

What's at Stake

Mining is a "massively important industry" that is needed to "facilitate development and meet the needs of humanity," according to a report by Brimco.

The market's value worldwide was US$2.14 trillion in 2023 and is expected to grow by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.7% to US$2.78 trillion by 2027, making it "an extremely lucrative area to invest in," the report said.

"The sector is also well positioned for further expansion as it relies on continual advancements in technology, such as automation and artificial intelligence, in order to maximize efficiency and maximize profitability," Brimco noted.

When it comes to increasing exploration budgets to look for those resources, Canada led the pack in 2021 with more than US$800 million, according to Statista.

In addition to their traditional uses, precious metals like silver and base metals like copper are also essential to the transition to clean energy. Silver is nature's best conductor of electricity, and there is more than three times as much copper in an electric vehicle (EV) as a traditional one. Rare earth metals are essential for magnets needed for everything from computers to wind turbines.

Durendal's Mintram said its approach will integrate with explorers' drone data, geophysical results, and other information and will make exploration as much as 90% cheaper.

"The idea is to spend money extremely effectively on the ground where you need to spend it," he said.

| Want to be the first to know about interesting Base Metals, Gold, Critical Metals, Silver and PGM - Platinum Group Metals investment ideas? Sign up to receive the FREE Streetwise Reports' newsletter. | Subscribe |

Important Disclosures:

- Durendal Resources Inc. has a consulting relationship with an affiliate of Streetwise Reports, and pays a monthly consulting fee between US$8,000 and US$20,000.

- As of the date of this article, officers and/or employees of Streetwise Reports LLC (including members of their household) own securities of Durendal Resources Inc.

- Steve Sobek wrote this article for Streetwise Reports LLC and provides services to Streetwise Reports as an employee.

- This article does not constitute investment advice and is not a solicitation for any investment. Streetwise Reports does not render general or specific investment advice and the information on Streetwise Reports should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Each reader is encouraged to consult with his or her personal financial adviser and perform their own comprehensive investment research. By opening this page, each reader accepts and agrees to Streetwise Reports' terms of use and full legal disclaimer. Streetwise Reports does not endorse or recommend the business, products, services or securities of any company.

For additional disclosures, please click here.